How to Draw an Orchard Tree

"As the woods are the same, the trees standing in their places, the rocks and the earth... they are always different too, as lights and shadows and seasons and moods pass through them." Emily Carr

Trees are an endless source of inspiration for me. So many unique combinations of color, light, shadow, form, and other elements (Emily Carr put it well in the quote above). In this post, I provide guidance on how to paint them. I cover:

- Idealized Views

- Simplification

- Purpose

- Color and Light

- Brushwork

- Style and Theme

- Composition

- Nature Is Not Perfect

- Different Mediums

- Step by Step Guide

- Additional Readings

Ivan Shishkin, Pine Forest. Unfinished Sketch, c.1894

First things first—you must break free of any idealized views you have about trees. That is, what you think a typical tree looks like.

Take a moment to shut your eyes and picture a tree in your mind. What do you see? That tree is not based on reality, but rather the ideas and experiences you have had with trees throughout your life.

For me, and many others I imagine, I see a tree with rich umber wood and luscious green leaves. Some trees look like that, but not all!

These idealized views may seem harmless, but they can work behind the scenes to bias our decisions and paint things that are not actually there. I see it all the time in beginner paintings—they are unsure about the color of the leaves, so they default to green, even if the leaves are warm yellows and oranges.

Leaves are not always green. Wood is not always brown. The sky is not always blue.

Be careful about letting your idealized views dominate how you paint. Paint the tree as you see it.

I will show you what I mean using the following reference photo:

The trees in the foreground are dark and underexposed in the photo. Because it is hard to make out any color, my mind defaults to green and brown. It seems the more ambiguous the colors, the more my idealized views take over. Regarding the trees in the background, beginner painters would be prone to overusing green and underusing yellow and orange.

A tree is a complex arrangement of shapes, lines, colors, and other elements. You must learn how to simplify this information to make any sense of it and paint a coherent picture. Even realists like Ivan Shishkin simplified to some extent.

If you could only see basic color shapes, what would the tree look like?

For example, take this reference photo:

This is a complex scene, with countless leaves, branches, shadows, highlights, accents, and colors. Not long ago, I would have put this in the "too hard" basket as my untrained eyes would have been overwhelmed by information. But now, I am able to tune out the noise and narrow down on the important details.

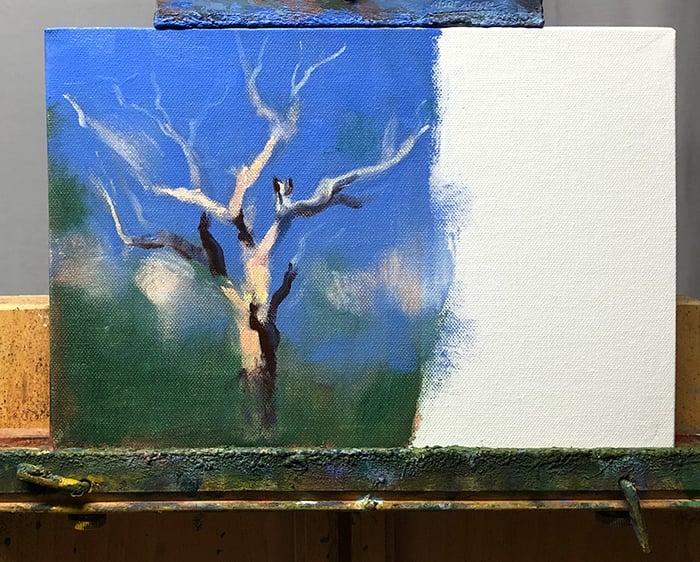

To give you an idea of what I see, below is the start of a recent study. Nothing more than basic color shapes. It took me about 10 minutes to get to this stage. Yet, even with such primitive detail, there is a quality of realism to it. That is the beauty of narrowing down on the important details and getting them right.

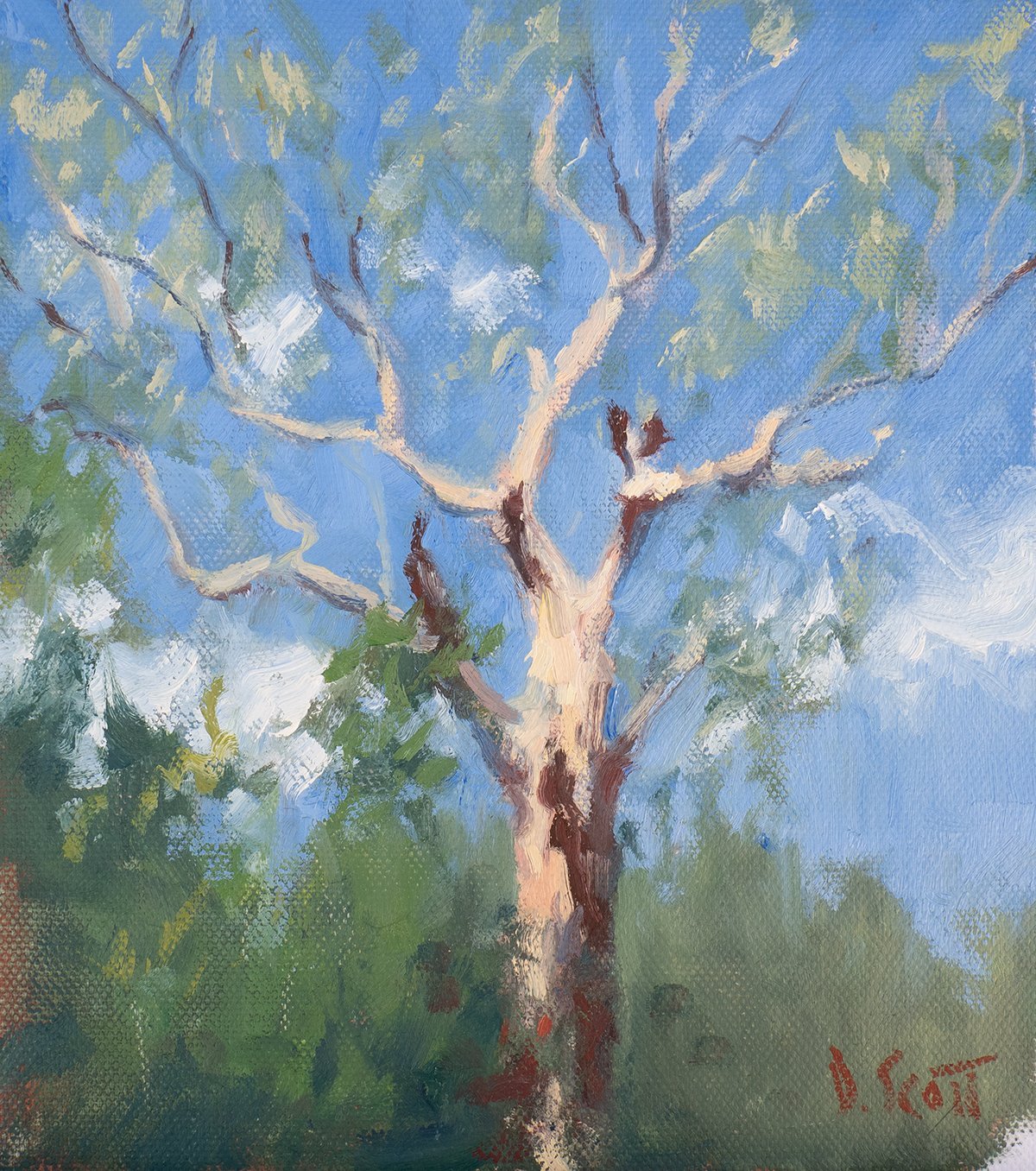

Below is the end result. Keep in mind this is just a small study done in preparation for a larger work (to be revealed shortly, along with progress shots).

Dan Scott, Tree in Perspective, 2020

I have also been playing around with filters in Photoshop to simplify the noise without picking up a brush (see the two examples below). But this is a matter for a separate post.

Once you see the tree in terms of basic color shapes, the rest is much easier. As long as you stay true to these basic elements, your tree will end up looking somewhat realistic. The amount of detail you use from there is up to you. If you enjoy getting lost in the detail, by all means, paint every leaf and branch. But you do not have to.

Here are some questions to help pull key details from the sea of information:

- What is the lightest light/darkest dark?

- What is positive/negative space?

- What is the hardest edge? (The softest edge is, by nature, difficult to spot).

- What is the focal point?

- What is the most saturated color?

If you want more examples of simplification, check out the work of Sir Arthur Streeton. He was a master of it. His paintings appear fresh and spontaneous, yet there is a remarkable sense of realism. In the painting below, notice how he intricately rendered a few trees in the bottom right. This almost fools you into thinking the rest of the painting is equally detailed.

Arthur Streeton, The Purple Noon's Transparent Might, 1895

The tree's purpose will influence how you paint it. A feature tree requires more attention than a background tree. Sounds obvious, but many aspiring artists overlook this idea.

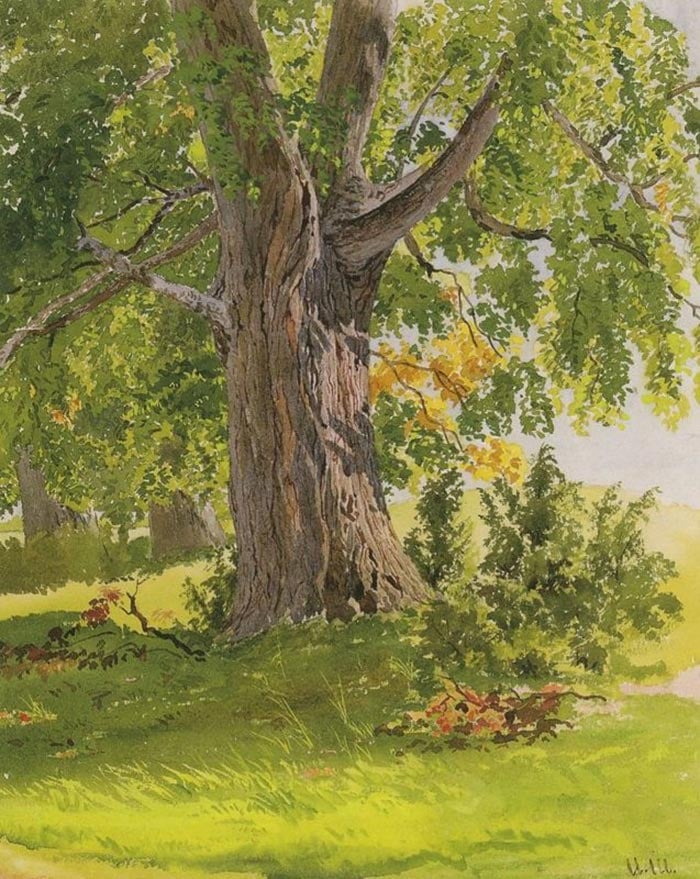

TakeOak on the River Bank by Isaac Levitan (below). The tree in the center is the focus and Levitan painted it accordingly. Subtle color changes, light and shadow patterns, a sense of form, rendering of individual branches and leaves.

Isaac Levitan, Oak on the River Bank, 1887

In my painting below, the amber tree is the focus and therefore required more detail and color variance. The other trees in the painting are really just two-value shapes; no mid-tones, no intricate branches, no subtle color changes.

Dan Scott, New Zealand, Amber Tree, 2019

In Claude Monet's painting below, notice the varying level of detail on the trees. The closer the trees, the more detailed they are.

Also, look at the tall trees shooting up into the sky. The contrast between these trees and the sky (dark green against light blue) is much sharper than the contrast between one tree and others (green against green). Areas of sharp contrast stand out and require more attention, hence the intricate linework and rendering of individual leaves.

Claude Monet, View Near Ruel-Le-Havre, 1858

"If you see a tree as blue, then make it blue." Paul Gauguin

There is no color recipe or formula for painting trees. But I can give you some general tips:

- Most of your color questions can be answered by the light. What is the light source? How strong is it? Where is it coming from? What color temperature is it? Is it direct or diffused by clouds?

- What are the lightest, darkest, most saturated, warmest, and coolest colors?

- Pay close attention to changes in color temperature. Are the lights warm compared to the darks?

Arthur Streeton, Sunlight (Cutting On A Hot Road), 1895

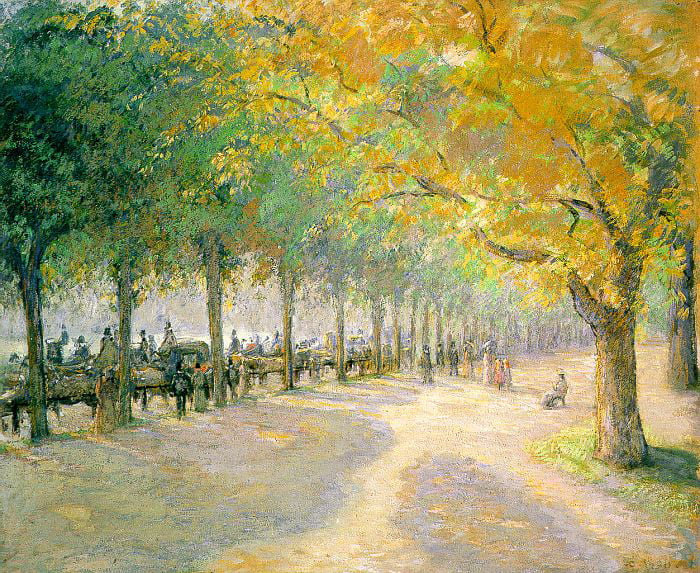

- Broken color can give the illusion of detail. Refer to Camille Pissarro's Hyde Park, London:

Camille Pissarro, Hyde Park, London, 1890

- Do not try to capture every subtle change in lightness. Simplify the value structure.

- Ensure you have enough color variance. Again, leaves are not always green! Take advantage of yellows, reds, oranges, blues...

George Inness, Autumn Oaks, c.1875

- For greens, I often start with viridian and add yellow to make it warmer or blue to make it cooler.

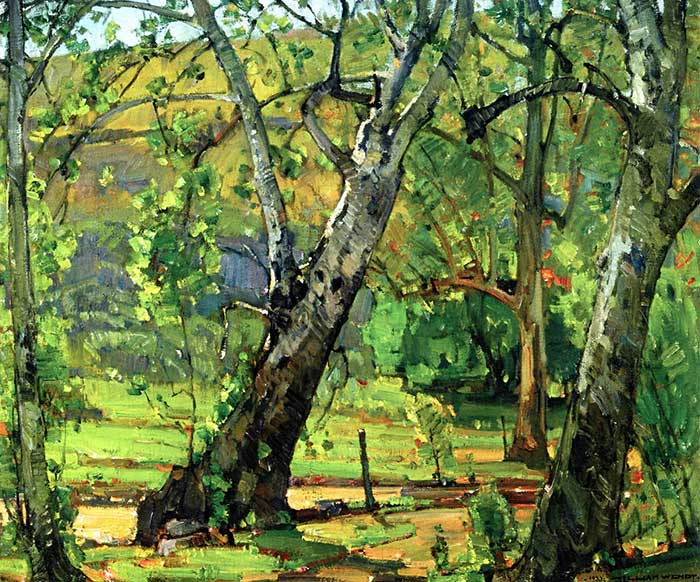

William Wendt, A Grove of Trees, 1933

- To paint lighter colors, be careful about adding pure white. Pure white makes colors lighter, weaker, and cooler; this can work against you when painting landscapes. Consider using yellow to lighten your colors.

I generally try to match the nature of my brushwork to the nature of the subject.

Is the bark rough and textured? Use rough and textured brushwork. Or even a palette knife.

Are the leaves delicate? Use delicate brushwork.

Are the leaves and branches dense? Use solid brushwork or layers of broken color.

As for what brushes and tools I use: whatever gets the job done. There are no rules. In my tree study shown earlier in this post (Tree in Perspective), I used filberts, flats, rounds, a palette knife, the tip of my finger, my fingernail, and paper towels.

The tools are there to help get the job done, not limit you in any way. Do not default to the fan brush whenever you need to paint a leaf.

To see what I mean, I suggest you check out Australian artist Ken Knight. Here is a video of him painting. A perfect example of using anything to get the desired result.

You need to consider the overall style and theme of your painting. Consistency is key. It does not matter how well you paint a tree, or anything for that matter, if it does not fit with the rest of the painting.

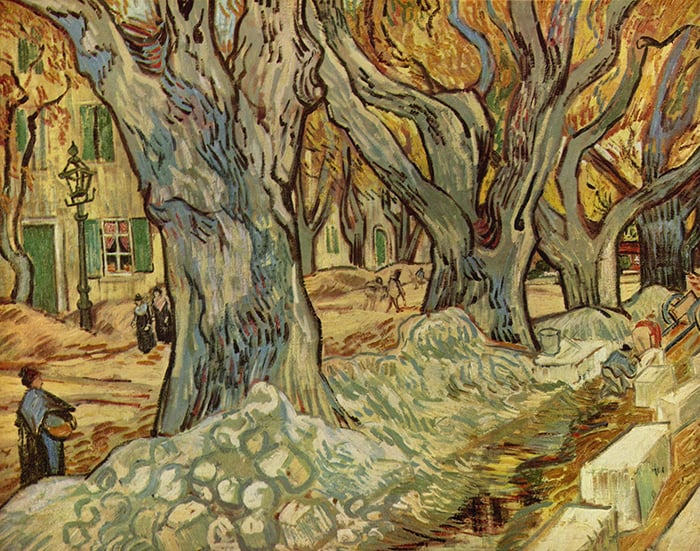

Vincent van Gogh took a stylized approach, using bold outlines and directional brushwork to reiterate the contours of the trees.

Vincent van Gogh, The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy), 1889

Monet often used rough brushwork and broken color to weave the trees in with the rest of the painting. The challenge with this approach is retaining a sense of form and realism.

Claude Monet, The Olive Grove in the Moreno Garden, 1884

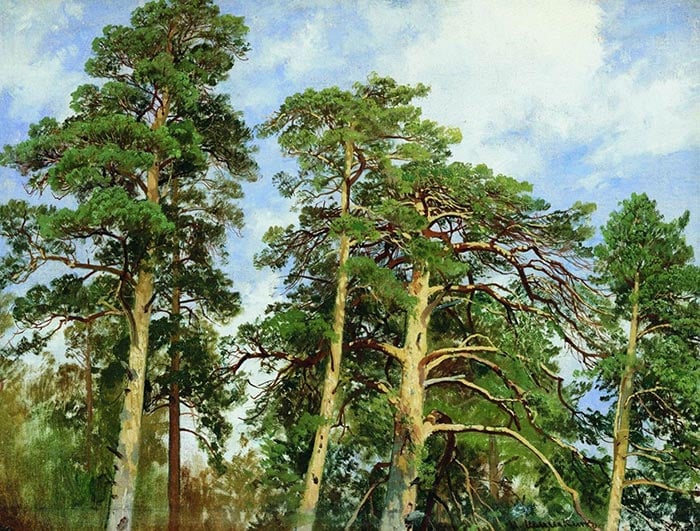

Ivan Shishkin's work is remarkably detailed. Therefore, it made sense for him to paint individual leaves and tiny branches.

Ivan Shishkin, Rain in an Oak Forest

Trees are a fantastic composition tool, particularly in terms of space, balance, and pattern.

Below are some examples, starting with John Singer Sargent's Olive Trees on Corfu. Notice the dance between positive and negative space. Positive space being space taken up by objects and things (the trees, buildings, and foreground); negative space being the space in between objects and things (the sky and mountains). There is also a secondary level of contrast, with the positive space being dark and the negative space being light.

John Singer Sargent, Olive Trees on Corfu, 1909

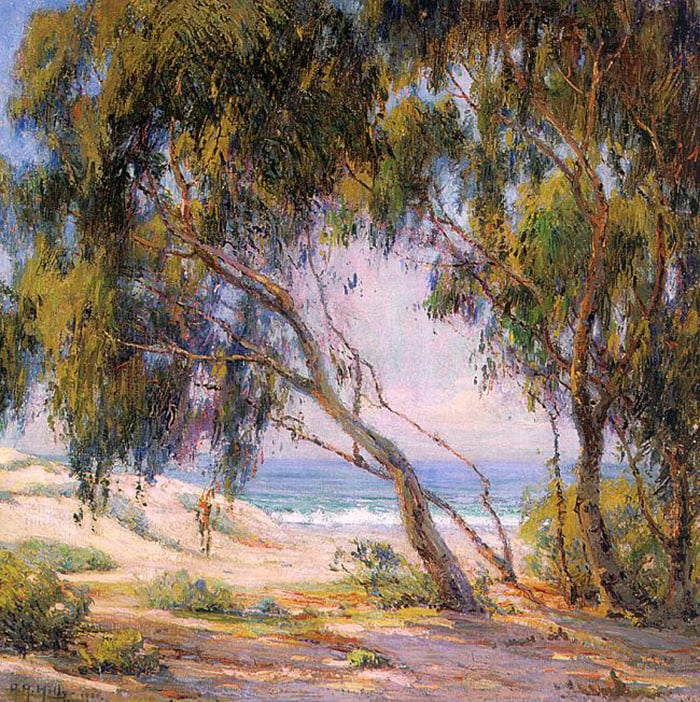

Here is another example of using trees to create an interesting dance between positive and negative space:

Anna Althea Hills, Sea View

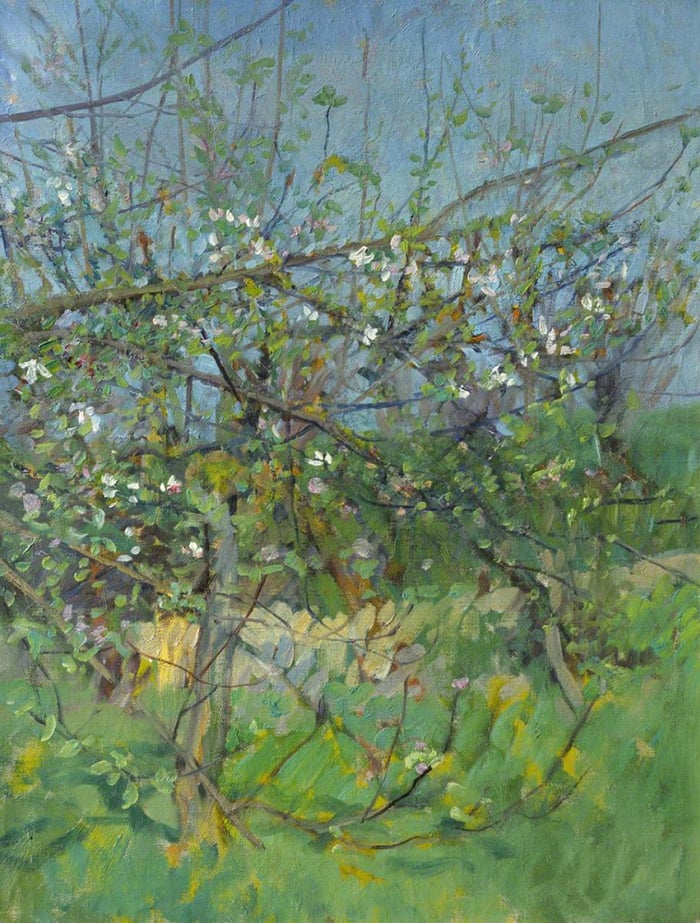

In George Clausen'sThe Cherry Orchard, the positive and negative space is woven together by the branches, leaves, and flowers.

George Clausen, The Cherry Orchard

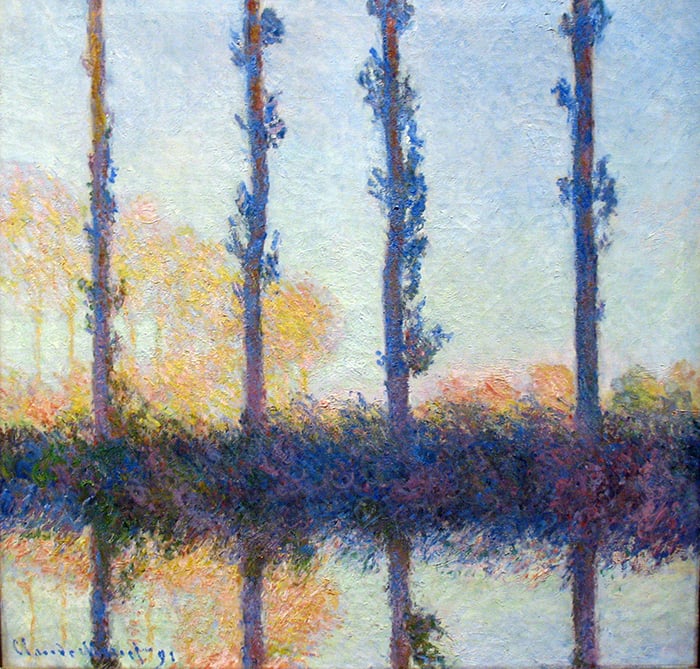

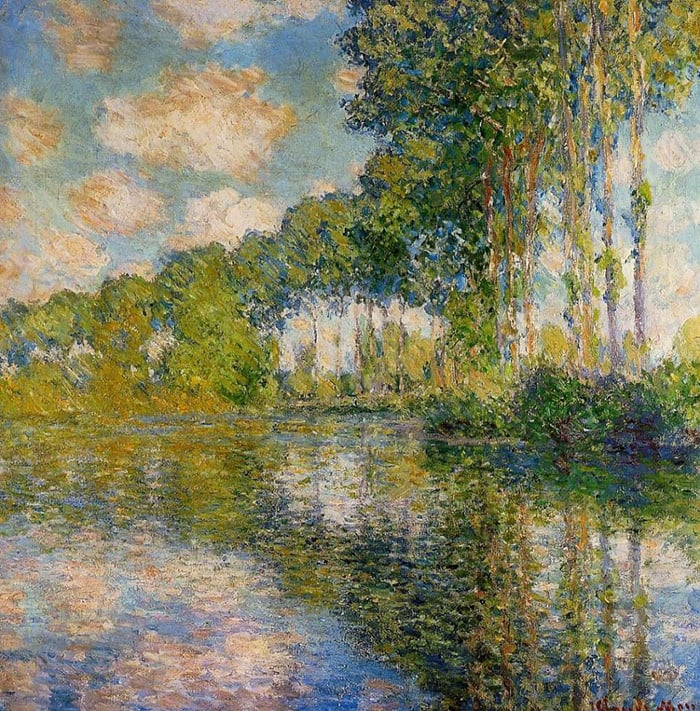

Monet often used trees to create a sense of rhythm (refer to the two paintings below).

Claude Monet, Four Poplars on the Banks of the Epte River Near Giverny, 1891

Claude Monet, Poplars on Epte, 1889

From afar, large numbers of trees unite into solid shapes that can anchor your composition. Refer to Pine Forest below. Hundreds of trees viewed from a distance appear to form a relatively solid shape.

Ivan Shishkin, Pine Forest, 1895

Trees allow you to explore changes in form, contours, and perspective. InOak, Lit by the Sun (below), the tree and its branches shoot up, down, forward, and back in perspective. This is reiterated by the shadows and contours.

Ivan Shishkin, Oak, Lit by the Sun

You can use trees to explore extreme perspective points, like looking upward from the foot of a tree (refer to the painting below).

Ivan Shishkin, The Tops of the Pines, 1890

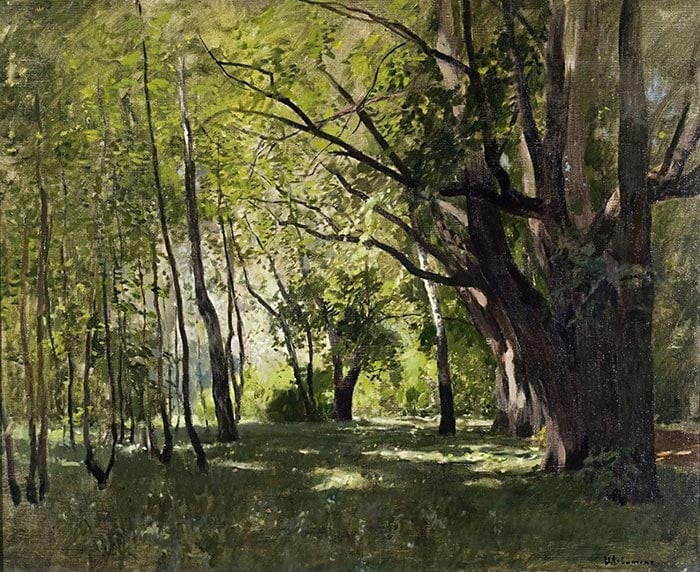

Trees often create interesting light and shadow patterns from light bursting through gaps in the canopy. This is known as dappled light. A common theme in many of Isaac Levitan's paintings, like the two below.

Isaac Levitan, In the Park, 1895

Isaac Levitan, Birch Grove, 1889

(You might be interested in my Painting Academy course. I go into more detail on how to design interesting compositions for painting.)

"If a painting of a tree was only the exact representation of the original, so that it looked just like the tree, there would be no reason for making it; we might as well look at the tree itself. But the painting, if it is of the right sort, gives something that neither a photograph nor a view of the tree conveys. It emphasizes something of character, quality, individuality. We are not lost in looking at thorns and defects; we catch a vision of the grandeur and beauty of a king of the forest." Calvin Coolidge

Nature is a forgiving subject to paint. No one will notice subtle departures from the subject—an extra tree branch, fewer leaves, a missing tree in the background.

You are not afforded this flexibility in portrait or still life painting. People will notice if you paint the nose wrong.

Isaac Levitan, Blooming Apple Trees, 1896

I paint in oils, but the information in this post can be applied to any medium. The techniques change, but the principles are the same.

Also, different mediums allow you to capture different sides of the same subject.

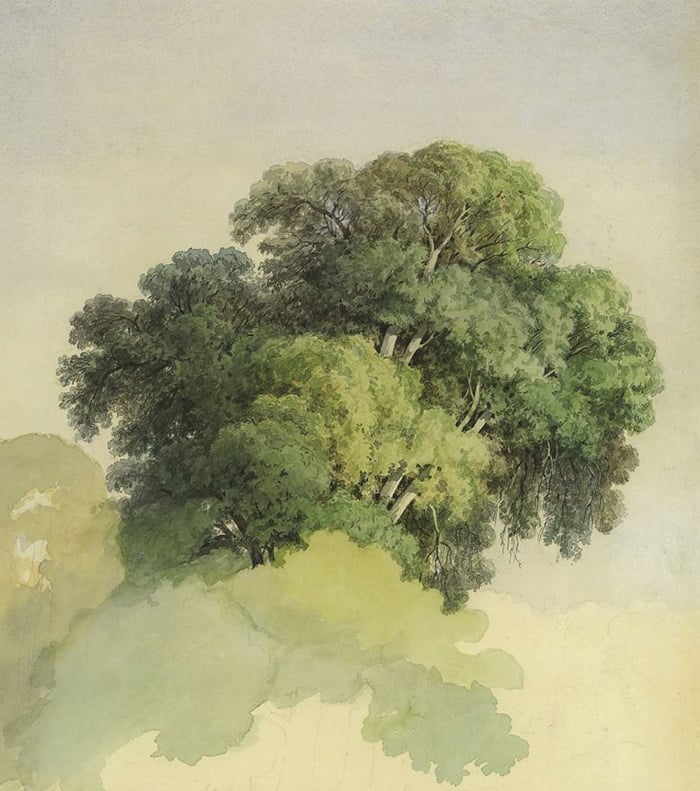

Watercolors: untamed, intricate, and transient.

Fedor Vasilyev, The Trees, 1867

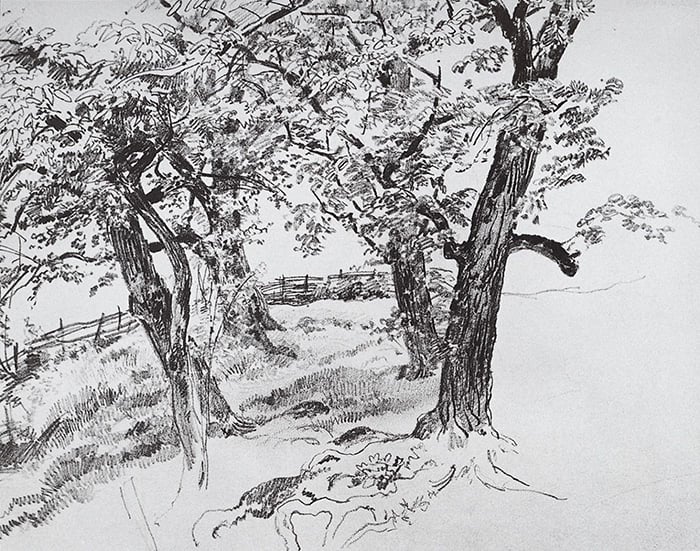

Pencil or pen: perfect for linework and contour drawing.

Ivan Shishkin, Trees, c.1870

Oils: thick, textured, dramatic, and versatile.

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821

So far, I have covered high-level principles for painting trees. But I understand some of you are looking for more of a step by step guide. So here is mine:

- Indicate the general positioning, size, and shape of the tree. This may be a basic sketch, color stain, or negative painting (lifting paint from the canvas with a cloth or rag).

- Capture the important lights and darks.

- Block in any leaf masses.

- Refine what is on the canvas.

- Add intricate details (individual branches, leaves, highlights, and dark accents).

Keep in mind that what works for me, might not work for you. You may also want to check out my "On The Easel" posts to see my painting approach in action.

Vincent van Gogh, Mulberry Tree, 1889

Thanks for Reading!

Thanks for taking the time to read this post. I appreciate it! Feel free to share with friends. If you want more painting tips, check out my Painting Academy course.

Happy painting!

Dan Scott

Draw Paint Academy

morwoodmysinsiging.blogspot.com

Source: https://drawpaintacademy.com/trees/